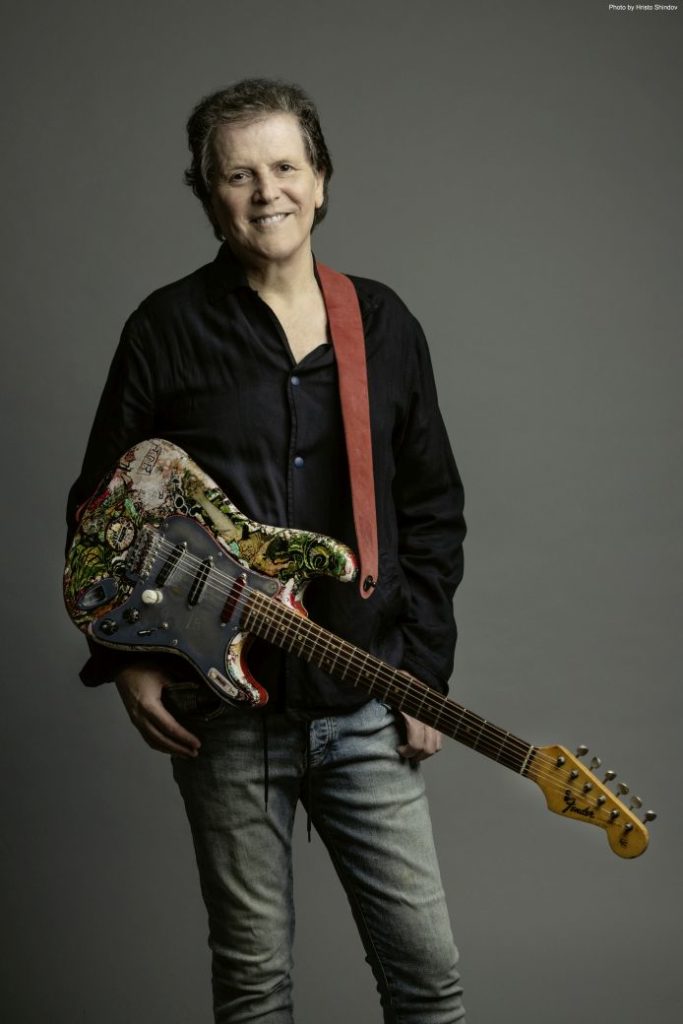

He wrote his biggest hit single on the toilet, taught Steven Seagal to play Hendrix and has scored blockbuster films. And now, after 34 years, Rabin goes solo again.

The man who is credited with having defined the sound of the 80s, Trevor Horn, was helped by another Trevor. Namely Trevor Rabin. This was done via a song Trevor Horn still believes is the best song he’s ever been involved with, the mega hit Owner of a Lonely Heart, which went to the top of the Billboard charts in 1984. It was written by Rabin and was worked on for over a year in the studio before Horn was satisfied.

From Cinema to Yes to cinema

The album it was taken from, 90125, sold eight million worldwide, three of them in the US alone, becoming Yes’s best-selling album of all time. Trevor Rabin had teamed up with Yes founder and bassist Chris Squire, Yes drummer Alan White and original Yes keyboardist Tony Kaye (who quit the band in 1971) and formed a new group, called Cinema. When original Yes vocalist Jon Anderson joined the band just before the album was finished, there was no going back. Yes, who disbanded in 1981, were back. With this new guitarist and main songwriter.

For many years, Rabin was in certain quarters of the Yes fan base accused of destroying the band, but what he really did was save the band. The band would most likely not exist today without him, and over the years more and more people have come to realise this.

Rabin is an extremely skilled musician and songwriter. Not only is he a sparkling guitarist, keyboardist, bassist, and a solid vocalist. He can also arrange and write scores and is as progressive as many other prog bands.

In addition, he has written film music for Hollywoo since 1995 (Armaggedon, Deep Blue Sea, Con Air, Gone in 60 Seconds, National Treasure, Snakes on Plane and many more). This has meant that he has had little time to make new solo albums. Before joining Yes, he had released four, and he released his last vocal solo album in 1989. In 2012, he released the instrumental jazz album Jacaranda.

Now, however, there are full vocals again, and Rio (named after his grandson) is a true solo album, where he has done almost everything himself, including the cover. Lou Molino, Vinnie Colaiuta Rabin’s son Ryan Rabin is on drums and percussion. Dante Marchi and Liz Constantine are doing backing vocals. And what a fine record it has turned out to be.

Sushi and jam

One drizzly Tuesday evening in northern Norway, I connected with Trevor, who was in his home in LA, via Teams to talk about the new album. He’s first comment was about my background photo which I took at a beach not far from where I live. It’s a nice display of Aurora Borealis (northern lights), a full moon and the sunset.

– It’s no doubt you live in northern Norway, he said. – That’s amazing!

– That’s a good start because I was going to ask you about that this. You have ties to Norway, don’t you?

– My brother-in-law lives there, and his children live there. And I know Oslo quite well. Obviously, I’ve played in in Oslo several times and I love the city. Especially that ice cream you can buy there in places along the roads. It’s the best ice cream.

– Another coincidence thing is that today I randomly ran into an old high school friend of mine. And as he was leaving, he said “ohh. By the way, I still have your VHS copy of 9012Live”, the concert video you did from the Yes tour in 1984 – 1985.

– Oh, that’s funny.

– What are your memories of that period?

– The majority of the music on that (90125) album had been written by me before I even met the guys in Yes. At the time I was on a development deal with Geffen Records. But they dropped me like a lead balloon after hearing the songs. Then I started sending out tapes, and Phil Carson responded. He was working at Atlantic, which led to me being introduced to Chris [Squire] and Alan [White] and that’s how it all started. So, I have a very kind of romantic memory of Chris, Alan and me meeting at a sushi restaurant. Chris turned up late, as usual. These are very good memories.

– I’ve heard that you went from that sushi restaurant to Chris’s house and had the worst jam ever.

– Ever! It was absolutely dreadful. But we finished and we looked at each other and said: “That was horrible, but something feels right here.” And then we decided to continue and quickly it started to sound good, you know?

Writing a hit single on the toilet

The lead single from 90125 was the number 1 hit single Owner of a Lonely heart which put Yes back on the map and is today a bona fide classic that to this day is constantly played on radio, music video channels and in video games.

– Is it true that you’re you wrote Owner of a Lonely Heart on the toilet?

– It’s absolutely true. This was in London before I’d moved to Los Angeles. The acoustics were fantastic, and I remember writing the down the main riff which builds up the entire song, thinking “Oh, that’s pretty interesting”. But then I thought: “Maybe it’s not! Maybe it’s just a couple of notes strung together. Maybe it’s nothing?” But when I played it a little later, I still thought it sounded good. And then the next day I came back, played it again, and came up with the lyric “owner of a lonely heart” and I thought: “This is kind of cool”.

Trevor says what really did it for him was when he started sending tapes out after Geffen dropped him.

– One of the people I sent the tapes to was Ron Fair at RCA Records. He was a great A&R guy and went on to do great things. And I gave him the cassette and I remember he called me, and he said, “this is a smash hit”. He’s the first person who ever said “you’ve written a hit song” to me because I didn’t know whether it would be a hit or not. You never know that beforehand. I mean, you always hope so, or at least hope it’s good. It doesn’t have to be a hit as long as it’s good. But he was the first to say this was a hit song.

– The song’s producer, Trevor Horn said in his autobiography that went on his knees and begged Yes to record Owner… because you guys didn’t want to do it. Is this true?

Trevor smiles.

– Umm, well I guess when you’re writing a book there can be some kind of fiction in it. You have leeway, right? So, no. I was pretty clear on that this song, even if it was finished very late in the project, that it would be the key song for the album. I didn’t want much changed on it, so I was very protective of it. I remember Jon Anderson walking past Trevor Horn when it was in the final mixing stage and nearly done, saying to Trevor: “You know there’s very little change structurally in this song”. He said it like it was an insult. But Trevor Horn turned around and said: “That’s a real compliment. Thank you!”.

From teenage star to nobody

Trevor Rabin started out as a child prodigy on piano, and later taught himself how to play guitar. As a teenager he was the vocalist and main writer for the band Rabbitt in his native South-Africa. They were as big as The Beatles in their home country and had enormous success.

– How was it going from that to coming to Europe, even being dropped by your record company after a while?

– I’m going tell you a story because you’ve basically led right into it, and you don’t even know it. I arrived in London after leaving Rabbitt. We went out on top, and I felt we were oversaturated. I arrived at Heathrow and walked through the airport with a friend of mine, who is a publisher. Then I saw a group of girls coming towards us. They were schoolgirls in school uniforms, and I immediately kind of turned my head to hide, thinking “God, if they see me, it’s going to be a whole incident”. And my friend looked at me and he said, “What are you doing?”. I explained and he said: “Trevor, you’re in England, you can’t even get arrested!” And suddenly reality hit me.

– What made you decide to leave South Africa? Was it the fact that you had no chance of making it abroad because of Apartheid?

– There had been some unfortunate things happening between the band and the record company. We were having problems, and we were signed to a label in in America, Capricorn Records, and were looking to sign to a label in England. My father represented us as a lawyer and him and me went to England to speak with the English label. But it turned out that the management in South Africa were very nervous about what was happening, politically, around that time., And they were not being very ethical in how they dealt with things. So, when I came back to South Africa with pretty good news, I realised that the whole thing had been tainted by management. Then I just decided that’s it! I’m leaving. But it was unfortunate. Thankfully the bass player and drummer are still close friends of mine. We still have a fantastic relationship.

He says it also was time to leave.

– South Africa was great for the band, but we were small fish in a big pond, and I definitely wanted to pursue having a career in the rest of the world.

The Kinks

Shortly after arriving in England, Trevor did his first solo album. Before he met up with Chris Squire and Alan White to form a band, he did three solo albums.

– The first album was done in the late 70s, after Rabbitt. So that’s where I first started to spread my wings. While working on the second album I’d been in England for a while, and it was kind of a confusing period. I’m kind of happy with some of it but it was an album where I was pressured for time by the record company.

On his third album, Wolf he had a star-studded cast.

– When I did that album, I sent tapes to people like Jack Bruce and Simon Phillips asking if they wanted to play on it. And them being positive about it was really exciting for me and I think Wolf was probably my favourite experience of those three albums.

–You got some real top-notch musicians on that album.

– Jack was phenomenal to work with. And Mo Foster who just passed away was a great addition. And Simon Philips on drums… You know, what can you say about, Simon? I’ve always I’ve been lucky enough to work with some unbelievably good musicians. Not least on my new album. In addition, I had Manfred Mann on Wolf. That came about because I co-produced his previous album before I did mine, and we were and still are close friends. Doing that album was just an incredible experience and it was all done at Cox Studios. Ray Davies [from The Kinks] ended up co-producing it with me. All in all, it’s a really inspirational album for me.

The sequel

After touring for two years with 90125, Yes started to work on a much anticipated follow up in 1986, It would take two years for the album to be finished. I ask Trevor if it was a difficult time for the band.

– It’s funny because that album… You know, I’ll digress a bit. It took over 30 years between my previous vocal solo album and this one. But when I look back on it, it’s like “What happened?” And if I look back a bit more, I see that I’ve done the music for 50 films and some TV shows. One should think I wasn’t ready to sing, but the good thing is that my voice is in great shape because of touring with Rick Wakeman and Jon Anderson for a long time. That meant this album happened at a great time for me, and I managed to keep it fresh. I had not signed any record deals or anything and I was just making a record for me.

And, Trevor continues, this brings us back to Big Generator.

– The way the first album (90125) with me, Chris, Alan, Tony and ultimately Jon happened was very peculiar. We rehearsed together for a long time as a fourpiece and then Jon joined right at the end. So, what he did was work on existing material, which is kind of a peculiar situation. When it then it came to Big Generator we were starting all fresh with each other. And we kind of looked at each other and said “OK, how do we do this?”. On the previous album we did existing songs I had worked on for years. And I think it’s the same for any band who has an album that does well. You spend your life doing that first album, but on the second album you suddenly have like 12 weeks to come up with something.

The process took much longer than 12 weeks. Chris Squire is on record saying that he and Alan White did the bass and drum parts 18 months before the rest of the album got sorted out. And the way it got sorted out was that Trevor in the end took the reins.

– Luckily, I think we got away with it. I love some of the material that landed up on Big Generator. But it was a tough process. In fact, it took me 12 weeks to mix the album because everyone had kind of abandoned ship. Trevor Horn had spent some time on the album and then we parted company before Paul de Villier came in when we went to LA and spent time on it. And then when he also departed it was like, “OK, I guess I’m the last one standing”. So, I mixed the album and that was the best part of the album for me because I really enjoyed mixing it. But it was a tough record.

– I listened to it the other day and I really enjoy that album, especially Shoot High, Aim Low. I love that song.

– That’s my favourite track on the album, together with Love Will Find a Way and a couple of others. There are some moments where I thank that maybe they shouldn’t even been on the album, but you know, that’s the way it goes sometimes.

My next question was about Love Will Find a Way. You wrote that for Stevie Nicks, didn’t you?

– I wrote that for Stevie Nicks, and it was the first track that I’d written a string arrangement for. Well, I did write some string arrangements before this, but this one I was really happy with. But you are right, it was written for Stevie Nicks. But then Alan heard it and said: “What is that?” I said it’s just a song I’ve written for Stevie and Alan said “Oh, no, we should do that”.

Back to solo

After touring Big Generator Yes went on a hiatus in 1989. Jon Anderson said he was disillusioned with being sidelined in his own band and left and brought together the Yes 70s alumni band Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe. Trevor on the other hand did what would be his last solo vocal record before Rio that is coming out now.

Was Can’t Look Away an attempt to get out of the difficult situation with Yes, or were these songs that you didn’t feel fit for Yes?

– No, I had signed a solo deal with Electra Records, and I had gathered what I thought was some strong material that I’d written for myself, and which was never meant for Yes. So, when the band was on a hiatus, I was partly doing some stuff with Roger Hodgson (of Supertramp) but mostly I was writing and recording a solo album.

– I especially like Sorrow on that album.

– Yeah? I’m, I’m glad you liked that song because the idea was to have a South-African feel to it with a very happy sound, but also with a very, very sad lyric.

– You sing about the miner strikes going on at the time, didn’t you?

– It was about that and it was also about the fact that during apartheid, if you’re in the wrong area, you couldn’t live with your wife because of the Separations Act. It was a terrible thing. So, the song is about a person having to give their child away to his lover’s mother, because you couldn’t live together as a family.

– You did something similar on your second solo album. You have this great catchy track called Now but the lyrics are about homeless people in Los Angeles, I think?

– It definitely had a melancholy kind of message in it. And I remember finishing that song and being quite happy with it, but that the album was difficult moment in my career. It was very rushed by the record company.

Leaving Yes

After doing two full albums with Yes, and four tracks on the Union album where the aforementioned Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe band and Yes joined forces in 1991 to go on tour, Trevor left the band after doing an album called Talk in 1994. The band was then back to the 90125 lineup. Soon after Trevor’s departure Yes announced they were reforming their classic late 70s lineup. Since then, the band has had various lineups, and these days none of the band members Trevor used to play with are in the band anymore. Sadly, bassist and band founder Chris Squire and drummer Alan White died in 2015 and 2022 respectively.

– Did you ever get to see them live and experience the powerhouse that was Alan and Chris, whom you had played with for years?

– I did get to see them after had worked with them and… You know it was a different band and I was into other things, by then. So, me going to see them was more about hanging out backstage. I didn’t even think about music. I just wanted to go and say hi to Chris, who was like a brother to me, and to Alan and Jon of course.

Trevor says Squire approached him a number of times during the late 90s and 00s to come back to the band.

– I told him I couldn’t. I remember I told him at one time that I had just signed a deal with Disney for a three-film deal which was going to go over a number of years and I there was no way I could have done it. But Chris was a persistent *beep*, you know, ha ha!

All your basses are belong to us

After doing film music for seventeen years, Rabin suddenly released the all-instrumental album Jacaranda

– Why did you decided to do an an instrumental jazz album in 2012?

– I’ve never talked about this, but there’s a guy whose name is Hennie Becker. He’s probably the most brilliant musician I’ve ever worked with. I did sessions for him when I was a teenager basically, and there was one session where I arrived, and he said that the bass player hadn’t turned up. He didn’t know what to do because he had a full orchestra waiting. And said I had a bass in the trunk of my car and that I could play and then do the guitar session work afterwards. “Perfect”, he said and from that moment I did a ton of bass sessions for him. Anyway, the story I’m getting to is he had this unbelievable jazz band that used to play every weekend. And he did a lot of fusion and jazz, and he showed me how they could take a piece of music and extend it and do incredible things with it. He taught me so much about that. And I played bass in his band for many shows. Because of this I’d always wanted to do an instrumental record. And after doing so many films I felt it was time to do something for myself. So, I told my agent that I was going to take some time off. I was between films and had the time.

As with the new album Rio he didn’t have record deal before starting on it.

– I just I wanted to make this record. If was released, fine. If it didn’t get a release, fine. I just wanted to make it.

– Since you mentioned bass, your bass playing on the new album is superb.

– Oh, thank you so much. I never talk about it but as I just mentioned to you, I’ve played bass all my life. But then when Hennie got me to play, I started do bass sessions just as much as I did guitar sessions. And in Yes there was certainly no need for me to play bass. We had a guy who played bass, not too bad, you know. But it’s an instrument I’m as comfortable with as I am with the guitar.

– When the last Yes album you did, Talk, came out in 1994, there were some people saying that you played all the bass on that album. Is that true?

– Chris played, I’d say, 98% of the bass parts on that album. But when I wrote, for example, Endless Dream on that album, I played the bass on it because I was going to present the song to the band. And since it was all done digitally, there was no such thing as a demo. If it works, you can use it. It’s not like you’re using a cassette and then having to do it all over again. But Chris redid pretty much all the bass on Talk and added the Chris Squire thing to the music. There might have been a note here two in there where felt my playing was good enough and saw no reason for him to do again. But he is the bass player on that album. So, it’s not relevant.

Diverse and coherent

– I actually got Rio as a promo copy already back in August, so I’ve been listening to it quite a lot now, and I have to say this is your best solo work yet.

– Oh, thank you so much. I feel that, as well. But I I’m glad you say it because I really shouldn’t be saying it, haha!

What I like about it is that it’s very diverse musically but at the same time it doesn’t feel like a disjointed album.

– Funny you should say that because as mentioned earlier, I went into it without being concerned about a release or anything. If I didn’t get to release it, that didn’t matter. And I wasn’t with a record company at the time. So, I did the album. When it was finished, I talked to Thomas [Waber] from Inside Out Music. We were originally talking with him when we hoped to do an album with music from Jon Anderson, me, and Rick Wakeman in the ARW project. Obviously, that didn’t happen, but Thomas said that if I ever did anything, I had to call him first. And since I didn’t want to start a whole round with lawyers and managers sending the album out to a lot of record companies to get offers, I just played it to Thomas. It was simply because I have a strong feeling about the guy, and I just sent it to him and said: “Listen to this and let me know if you are interested.” And that was it. He liked the album. It was the easiest deal I’ve ever done in my entire life.

Trevor says it all shows that he just went into the album with the purest intentions: Having fun and creating the music he wanted to do without any pressure or constraints.

– As you pointed out, it’s very diverse. I even throw a bit of country in there. I love that kind of picking twang you find in that kind of music. Even a guy like Vince Gill, who people think is just a crooner is a great guitar player doing that style, which I love. Whenever I’ve played in Nashville, I always used to go and listen to bands playing in the clubs there after our own gig.

He points out that there is also stuff on the album that is obviously in his DNA.

– You have stuff like the more epic sounding works if you like. I just thought I was going to put it all together and hope for the best. And then I put my producer hat on, and I thought my voice was in pretty good shape. That is because I’ve been on the road for a while, and I got the singing muscles going again.

Trevor says even if the genres on the album are all different, it doesn’t matter as long as it all works together.

– I was a little worried about it, but I thought hopefully there’ll be enough there to glue it all together and make it sound like a cohesive, coherent album.

Cinematic country

– You mentioned country pickings. My favourite on the album is actually that track, Goodbye.

– Oh, wow. That’s a real compliment. Thank you.

– I just love the contrast between the verses and then this kind of power AOR rock chorus.

– It’s got nothing to do with country, no.

– Another song I really like is Oklahoma. It’s beautiful and is very cinematic.

– Thank you so much. That was inspired, obviously by the Oklahoma bombing in 95. And I really wanted to do it so that it just starts like it does and then just grows and grows until the end where it can’t grow anymore and it just ends, you know?

– Do you think you could have written a track like that before you started doing soundtracks?

– No. I might have been able to write something close to that, but the integrity if you like, of the orchestra and the instrumentation… I don’t think I would have thought like that before. Even though I actually won an award for best orchestral arrangement with Rabbitt back in the mid-70s. I put this big string arrangement behind the song Charlie, and I was amazed when I won that award. I thought that Hennie Becker should be winning that award, not me. And as we talked about earlier, I did some orchestral stuff on Big Generator. But definitely now, having done so many films it was very natural to me to do such an arrangement on Oklahoma.

– When you when you compose for a film, do it on the guitar, the piano or do you use computers?

– I’m giving my age away; I’m turning 70 next year so I’m kind of old fashioned. I simply write the score with pencil and paper. All this has changed very much in the last 40 years. In the old days, when Bernard Herrman, for example, wrote film music, everything would just be written out and thrown into the orchestra and there was no opportunity to play it to a director with synthesisers. Today you can have it sound so close to the real thing that way. But I maintain that however good your samples are, and I’ve got fantastic sounds, and no matter how well it’s done, compared to real people playing it is like comparing black and white to colour. It’s completely different because the human element is still important. And I hope that stays in and that AI doesn’t also take that away.

– I’ve interviewed several veterans in the music industry that in the later years have been working with people a generation younger than them. When I ask them if they deal out advice to the youngsters, they say no. They claim they have no clue of what’s going on in the music business today. Is that how you feel?

– Absolutely, 100%. It’s great to hear you say this. If I try and keep up with what’s happening it would be ridiculous. All I can do is do what I do but try and make it as fresh and inspiring and real as I can. I can’t do more than that.

Another reunion

Between 2016 and 2018 Trevor joined Rick Wakeman and Jon Anderson in did a tour under the monicker Yes featuring ARW. They released a live album and a Blu-ray concert film, where they performed Yes songs from the 70s, 80s and 90s. The plan was that they also were going to release new music, but this never came to fruition. I ask Trevor why it all fell apart.

– Speaking for Rick and myself, it was something we had wanted to do ever since we did the Union tour with Yes in 91. We had never been in Yes together at the same time, and him and I got on so well on that tour. So, we kept saying that we should really work together again, and the idea was just to do that. It’s funny because there’s a lot of talk about what happened with that project. The important thing is that we had a great couple of years together touring and playing.

He says he still talks to Rick all the time.

– We haven’t done any recording, the two of us, yet. But we have talked about doing an album where he plays piano, and I play classical guitar and maybe at some point we’ll do it. Time is always a problem. As we talked about earlier, Chris kept asking me many times about me doing something together with Yes again. But it would have been a problem because they already had a guitarist (Steve Howe) so that wasn’t going to work out. And I had these films that I was doing, so there wouldn’t have been time for me to do it anyway. And with Rick it’s same kind of issue. Also, we live very far apart but we are still very close friends.

Trevor hasn’t talked to Jon for a while.

– There’s no specific reason why we haven’t. We are still friends. I was hoping to see Jon at Alan’s memorial last year, but he didn’t turn up. So, I haven’t seen him for a while.

– When I spoke to Jon a when he did his last solo album, he said the reason ARW folded was just one of those things. Sometimes it just doesn’t happen.

– I don’t think it didn’t happen that would be my only disagreement. I think we did it and it was worth doing. I don’t look back at it and say “Hm, maybe we shouldn’t have done it because it didn’t work out”. I think it did work out.

– Oh, he didn’t say that regretted doing the tour. He loved the tour and everything. It’s just that when I asked him why you hadn’t done an album he said sometimes it just doesn’t happen.

– Ah, ok. Yeah, that’s a good explanation as any right there.

Steven Seagal and Jimi Hendrix

– Who did you look up to as film composers?

– Bernard Herman. I used to go and watch black and white movies and he did all this cool Westerns and lots of other films. He did just so much stuff. I remember story where he did some film with Hitchcock. He had worked with Hitchcock before, and he referred to the previous movie they did as terrible. And he thought Hitchcock would agree or something, but it didn’t go down very well. I just heard that recently. Anyway, he would be my favourite and is the guy I kind of tried to mould myself after.

– Is it true that you got into film scoring back in 1995 because you taught Steven Seagal how to play a Jimi Hendrix song?

– He he, yeah. I went through Red House by Hendrix with him, and a lot of other stuff. At the time I was trying to get into film, and it was impossible. And one night my wife and I went to a restaurant called Oasis. We’d been there before many times and the maître-d’ came up to me and spoke English in a very thick French accent. And I didn’t really understand him at all so I went back to him. I said “Sorry, what did you say?”. And then I realised he says Steven Seagal is a part owner of this restaurant. Steven knew I used to come there and had told the maître-d to ask me if I could come to Steven’s house and play some guitar.

Trevor said he absolutely would.

– And I thought in the back of my mind that maybe he had an agent I could call or something to help me get into film scoring. So, I went to his house, taught him some stuff and we played together. And then afterwards he said, “Oh, thanks, this was very kind of you.” We got on quite well. But Steven’s kind of a megalomaniac, you know. And he said to me, “Can I help you in any way in return?”. And I said that if he had an agent’s name or something, I’d appreciate it. I explained I was trying to get into film scoring and explained that I was very confident with orchestra and technology, the two things you need in a film score composer. And he said: “Well, I’ve just done a big movie which is going to be a blockbuster. It’s called Glimmer Man. And if you want to do it, you can.” And was like, “Oh my goodness, are you serious?” And he said: “Yeah, just call this guy.” And I called this guy from Warner Brothers, the head of music there, and he said to me: “What makes you think you can *bleep* do this movie?” And I just took a chance and was sure he was going to throw me out the office, and said: “What makes you think you’re going to *bleep* talk Steven Seagal out of it?” Because I knew what Steven was like. And I got the movie!

Jerry Bruckheimer

Even if the film wasn’t a big box office success, it did start the ball rolling in Hollywood for Trevor. Pretty soon one of the most powerful producers in Hollywood, Jerry Bruckheimer (Flashdance, Top Gun, The Rock, Crimson Tide, Con Air, Armageddon, Enemy of the State, Black Hawk Down, Pearl Harbor and the Beverly Hills Cop, Bad Boys, Pirates of the Caribbean, and the National Treasure franchises) called.

– What happened was that a music person working for Bruckheimer saw Glimmer Man and went to Jerry and said there was this quite interesting new guy in town. So, I was asked to come to a meeting. I think Jerry thought I was going to be 22 years old or something, but I think I was 40 something at the time. And the very next thing I did was Con Air.

That film was indeed a huge box office success, and since then Trevor did the next 13 Jerry Bruckheimer movies and then another 50 movies and TV themes and shows.

– So, thanks, Steven!

– Was this before or after you left Yes, or did you leave the band without any certain prospects?

–There was nothing! I left knowing I wanted to get into film, but no clue how to do it. After all the work I did on the Talk album, everything happened like this perfect storm. The record company went bust shortly after its release, the record didn’t do well, and the music industry was changing. And I thought about the fact that I had put all my energy into that record. I had embraced a whole new way of recording with software that wasn’t even ready at the time. I mean, I remember I had the developers coming in, writing code and stuff because it wasn’t working. I had four Macintoshes trying to control it. It was a bit of a nightmare, but it was also incredibly inspiring. So, when it came to the end of that album and tour, I felt completely worn out from it all. And I left the band.

Trevor then tried to get meetings with the film composer agents but found it very difficult.

– No one cared about a guy who’d been in a rock band. They figured such a guy was not going to be reliable. So, it just didn’t work out that easily. And that’s where Steven came in. And suddenly I was just very, very lucky, because I had nothing lined up after Yes. I just knew what I wanted to do.

– What’s your favourite movie that you made the music for?

– I think the movie called Remember the Titans. It wasn’t as successful as films like Armageddon or National Treasure, but it did well. I was also very proud of Armageddon and National Treasure. But I think Remember the Titans is the one.

– There’s one movie I know you were involved in that has a bad reputation, but it has been started to be reevaluated in recent years. That was the movie Rockstar.

– The score I did for that is very organic and very underplayed, there’s no orchestra. I used the guitar a lot and did different guitar sounds and I really enjoyed that. Still, I didn’t think that it would be recognised in any way in the music industry. And when I went to the premiere and out of the blue, I met David Foster there. He came up to me and said, “I just want you to know I love that score”. And I was kind of like: “Really? I love everything you do, David! You’re a genius, you know?” But he was so kind about it, and it was really inspiring to me. Little Steven also came up to me. He was so kind and nice, and he said, “Great score, man”. Before the movie opened, I was afraid that maybe I had underplayed it. Since it was a movie about music, I didn’t want to put too much of my own style into it. So, it was more organically done, and I left the premier feeling pretty good. So, I’m glad to hear it’s being recognised now. It’s a true story about based around Tim Ripper Owens who took over as vocalist in Judas Priest. It was a great story and I think it was well done.

Shooting the eagle

In the mid-2000s, an album called 90124 came out. It contained demo versions of a lot of the songs that ended up on 90125, Big Generator and Talk. When you listen to it you realise how finished many of the songs really were when Rabin presented them to the band.

– One the songs on there is an instrumental version the song Where Will You Be that sounds exactly like it does on the finished recording, except for Jon’s vocals. How much was the song changed after you demoed it?

– That is the one song that was not recorded digitally for Talk because my demo that you hear on the record is something that Jon sang on top of. Chris played a couple of bass notes and Alan played a couple of drums. Otherwise, it’s absolutely identical. You are right.

– There are also two versions of a song that eventually became Owner of a Lonely Heart on it.

– That’s right. And when we started doing the record, the first version wasn’t working for anybody in the studio. So, I tried a couple of other things, which didn’t help. And then the next version you hear on 90124 is a version I did on a Revox tape recorder in the living room of a small apartment Where I was staying. I just took a microphone and recorded the acoustic guitar and that’s how the new verses were written. And then Jon changed some of the lyrics on it.

– Yeah, Trevor Horn said he hated the “the eagle in the sky” line Jon threw into the song. He said he and engineer Gary Langan added a shot in the song after the word “eagle”, to shoot it down.

– Yes, we did shoot the eagle down. That was something Trevor, me and Gary came up with. We all hated that lyric, including Chris. And we thought it was hilarious to shoot it down. We found it totally laughable.

I hope you forgive me for saying this, but I find the video laughable too.

– Ohhh, I hate that video. I absolutely loathe it. I hated everything about it. The thing that was so infantile about it is everyone changing into animals and the technology wasn’t there. So, it looks ridiculous. I remember calling my manager and I said “Can we redo this video? I think it’s just horrible!”. And he said: “The record company has spent a lot of money on this, even on helicopters.” And I said, “Well, maybe there should have been a storyboard beforehand because it makes no sense”. I’ve always said that I hate that video.

The video was made by the people in Hipgnosis, who did legendary record covers for both Pink Floyd, Yes and a whole bunch of other artists.

– They should have stuck to making album covers.

Selling your material

– I saw your name on a list of people who have sold their music publishing. And I saw you had sold 3528 film queues and songs to a company called Primary Wave.

– That’s right. It got to a point where the industry had changed so much with the streaming stuff. And no one in Congress seems willing to go forward to try to protect songwriters. And then I was presented with this opportunity. It’s like a sexy thing for investors, these days. A lot of people are doing it. So, I saw it as a great opportunity to get out of having to do all the work managing my publishing catalogue. It also gave me some cash in the bank. And then I see Genesis did the same thing, and I said “Hey, didn’t get that amount”, ha ha!

– Yeah, when I see the sums these companies pay for the publishing catalogues, I wonder how they are going to recuperate those costs.

– I don’t think they will. So, I was glad to get out when I did. But you are right, I really don’t understand it because what they do is calculate annual earnings from your catalogue and then you negotiate how many years you should multiply that with. And then you agree on a figure. I don’t know how they’re going to make back paying Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen half a billion dollars!

– I saw saw today that Katy Perry had sold her catalogue for $250 million.

– That’s just insane.

Super producers

– Back to Rio, will you be touring this release?

– At the moment the focus and the emphasis are on doing what you and I are doing right now.

– If you do go on tour would it be the same guys that toured with you, Jon and Rick on the ARW tour?

– I would definitely ask Lee Pomeroy, who is a phenomenal bass player as well as the main drummer on Rio, Louis Molino. Without question. Although very sadly, his wife just passed away. So, this is certainly not something I would bring up with him right now. But I would absolutely hope he’d be the drummer.

– Trevor Horn isn’t the only super producer you’ve worked with. On Can’t Look Away, you had Bob Ezrin as your producer. What was it like working with him?

– I think he’s my favourite guy I’ve worked with outside of people I’ve been in bands with. I think he’s just a brilliant producer. He’s worked with everybody, and he is a great musician and writer himself. And smart too.

– Paul Stanley of Kiss said working with Bob was like going back to boot camp.

– Absolutely. And Bob can do that. In one minute, he can do Pink Floyd and in the next minute he can do Kiss and Judas Priest. And then he does an album of with me! When we were starting to work on 90125we first had a meeting with Mutt Lange and then Roy Thomas Baker. Bob Ezrin was another guy that we were thinking of. But since Chris had worked with Trevor Horn on Drama(Yes album from 1980 where Trevor Horn was the lead singer) we went with him.

– Horn has said that joining Yes as their lead singer is just one of those stupid decisions you sometimes make in your life.

– That’s funny! Chris told me about the first show they ever did with Horn singing. Chris told him: “Alright, you go to the front and then you just sing”. By the third song Horn was hiding behind the drums. But he’s playing live now, apparently.

– He’s actually touring as the Buggles.

– Right? And apparently, he does Owner of a Lonely Heart which I think is a bloody cheeky, he he.

– He wrote in his book that he considers it the best song he’s ever been involved with, but that it took a lot of work.

– He was resilient with it, yeah. He was great guy to have on that record. And I have to say that after we finished working on 90125, before I started doing film, I worked a lot with Trevor Horn. He booked me for Seal and Frankie Goes to Hollywood and even Cher. He did a song that I played on and for Tina Turner. We had a lot of fun working together.

– That was on the Simply the Best album, right?

– Yes, and the Seal album was the very first one.

Prostate exams and pot

– You are in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame now. Correct me if I’m wrong, but you are the only South African to ever end up in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, aren’t you?

– Yeah, it’s quite funny. Phil Carson said to me: “When you go up and make your thank you speech, mention that you’re the first South African”. And I got up there said a few words, and I completely forgot to mention that! It was probably the most important thing to say.

– It can’t have been easy to remember much when you go on stage with Rick Wakeman

– Oh well, that was another thing. Rick was so funny on that night. I think it’s the best Hall of Fame speech ever, only tied with Alex Lifeson from Rush, where he went “blah, blah blah”.

– Yeah, that was quite funny. But the other two in Rush were not amused.

– I’m sure! But I could see both Jon and Bill Bruford next to me, and we were just laughing our heads off behind Rick when he was going on. I was sure I had to go to the bathroom.

– And then a couple years later, Steve Howe releases his autobiography. And in the first chapter he goes on about how much he hated Rick Wakeman’s speech.

– He did?

– He didn’t find it funny at all.

– I guess you must have a sense of humour to find it funny, right? I laughed my head off. I saw it online later I just couldn’t believe that he did it. And that’s what’s so funny about it is that this is supposed to be this serious night with all those boring speeches. And here he comes up talking about prostate exams. And when he finished the speech and caught my eye at some point, he just kind of winked at me. I don’t know how anyone could remain without a smile on their face during that speech. Rick is just so funny.

Trevor then tells me a story from the worldwide Union tour back in 1991.

– He didn’t want to fly, so he decided to buy a van and with the proceeds of what they normally would have paid to for the flights. He used it to drive around America with, and later he shipped it to the UK. It was ridiculous. I joined him on a trip from Canada to Buffalo. Of course, we had to cross the border and immigration stopped us. I was getting quite annoyed because their attitude was “OK, rock’n’roll band again. Find the pot!” And there’s nothing because Rick doesn’t do anything I don’t do anything. Then Rick started talking to these guys and 5 minutes later they were cracking up laughing. And they just waved us through. He’s just that kind of guy, you know?

Waking up the neighbours

– One track I forgot to ask about earlier was Tumbleweed. In my review I said it’s a kind of a mix of Imogen Heap, 50s jazz bands and the Yes songLeave it.

– That’s funny. The difference with Leave itand this song is that it’s just me singing on it for one thing. But it’s also a lot of chair chords, which I’ve never used before like that. And I just had a lot of fun doing it. It was a lot of work because it’s all me. I actually put things on the floor where I had to stand for different notes, so it was like many people were standing around the microphone. So, it took a while to do that.

– It sounds like this whole album has been a huge labour of love.

– One hundred percent! There’s nothing I did on this album that wasn’t just Love, you know? There is a guitar the solo at the end of the song Thandi, and it’s quite a thin sounding guitar. And the reason for that is I had a Marshall amplifier turned up to billion watts. My studio is acoustically compacted so no one can hear what’s going on from the outside. It’s also a separate building from the house, so it’s very secluded. But on this track, I decided I really wanted to just crank everything up and go nuts. So, I opened the door to add to the studio ambience. The result was that the whole neighbourhood heard the solo. My wife was out walking the dog and she rushed home.: “The whole neighbourhood can hear you!”

In the end, the idea didn’t work out.

– I also had a microphone outside in the garden just to try and get this huge sound. It turns out I just used the close mic. What happened was when I was playing it in the studio, the Marshall was so powerful that it ended up being the sound I got. But when the sound doesn’t go through the Marshall, and you’re just listening to it in the speakers, it’s not such as big sound. It ended up sounding thin. But I just had so much fun with it. I think I did about six different solos with this setup. I was just totally inspired.

He says all the solos on the album are completely improvised.

– Nothing is planned ahead. On the song Paradise, there was a couple of things that was worked out for the solo, but it was just a load of fun to do.

The follies of being young

– On the lead single, Big Mistakes, are you thinking back to your younger days in South Africa?

– Absolutely! I said to the bass player and drummer of Rabbitt that I should have called the song I Can’t Believe I’m Alive. Because I can’t believe we’re alive because the three of us got up to some antics. As you do when you’re a teenager.

– Yeah. I was thinking of back to my younger days when I heard that song. “That’s kind how it was”.

– Right?

– My son is 23 now, so he’s kind of moving out of that age where you don’t think about the consequences.

– Exactly. That’s the cutoff, around 24/25, right? When Ronnie from Rabbitt heard the song he said, “Are you talking about us?”.

– What are the the other Rabbitt guys doing these days? Are they still doing music?

– Ronnie, the bass player, still plays like a demon. He’s not playing live or on record or anything, but he just has his bass guitar, and he plays. They recently were asked to put a reunion tour together and they approached me, and I said I couldn’t do it. And then the guy who was going to manage it started promoting it with my name on the bill, so I had to send him a letter saying, “Don’t include me!” I’m not going to be there so he shouldn’t be exploiting my name. Don’t get me wrong. I would be happy to say good things about it. But anyway, it didn’t work out. But Neil the drummer got his kit together and was playing well and Ronnie was playing as well as ever. But the last guy, Duncan, couldn’t do it either. I think he is living in Vegas no, so it just didn’t work out for them.

Not all reunions are meant to happen, it seems. But Trevor doesn’t need one. After a remarkable career, soon spanning 50 years, which includes chart topping singles, millions of concert goers and millions of movie goers, he has an eager audience that will soon get to hear his best solo work, so far.

Rio is out on October 6th on Inside Out Music.