Join Jean-Michel Jarre and me as we take the second part of our walk through his ENTIRE discography of studio albums, while sitting talking in his flat in Paris. In this part we talk about making an album out of being the very first Western musician to play China, making a record that is pressed in one single copy and playing for 1.3 million people. And the pope! A fascinating talk with a true innovator, who is now out with a brand new album called Equinoxe Infinity.

This is the second part of a long interview I did with Jean-Michel Jarre in his flat in Paris on November 9th 2018. After handing the story in to the magazine I did it for, I realised that I had so much left over that I really wanted to publish. So here it is! You’re welcome! You can read part 1 here!

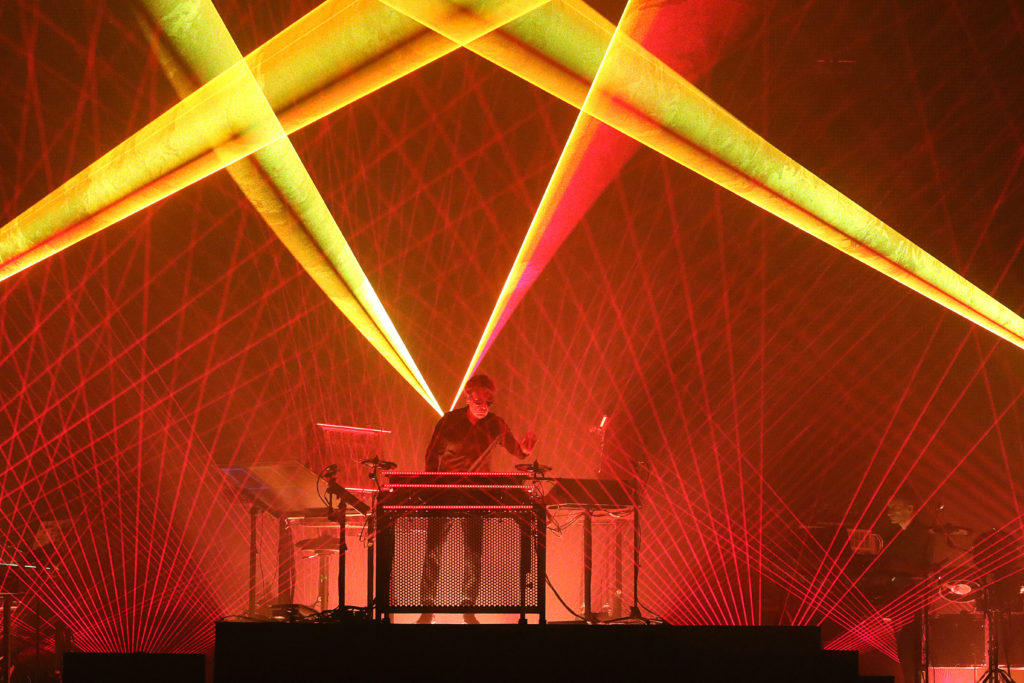

After releasing Equinoxe (1978), the followup to his breakthrough album Oxygene (1976), Jean-Michel Jarre did his first outdoor concert at Place de la Concorde in Paris. 1 million people showed up, and his first entry into the Guiness Book of Records was a fact. After recuperating, Jarre started the work on his next album. But this time with a different approach.

Magnetic Fields

Moving on to Magnetic Fields (1981). There had been a huge development in technology since your previous album, not least with the world’s first digital sampler, The Fairlight keyboard. And you sampled a lot of real life sounds, returning to your Musique Concrete roots. What can you tell me about the making of that album?

Moving on to Magnetic Fields (1981). There had been a huge development in technology since your previous album, not least with the world’s first digital sampler, The Fairlight keyboard. And you sampled a lot of real life sounds, returning to your Musique Concrete roots. What can you tell me about the making of that album?

– Any kind of art form is dictated by technology, and not the other way around. It’s always been like that. Vivaldi invented the violin and then he made the music he did. And Elvis did the music he did because in those days you couldn’t cut and edit, so everything had to be recorded in one take. And the songs had to be shorter than two minutes because that was the maximum length for a 78 record. And… what was the question again?

– Magnetic Fields, and…

– Yes, Magnetic Fields. First of all, I changed studios. The studio where I did Oxygene and Equinoxe, was not very far from where we are today, and it was in an old kitchen. I lived in a strange flat with two kitchens, so I turned one of them into my studio. It was a simple studio, but the sound was very warm. Then I had the means to build a professional recording studio, with big speakers on the wall and all that. And then the headaches started.

Jarre explains that in a big recording studio, the speaker becomes the room.

– And then, if the room is not perfect, you are trapped by that in terms of sounds, and you start dealing with that much more than with your music. In a home studio, you can get very accurate sound, because the speakers are close to your ears.

We return to talking about synthesizers again, and he says that mixing the Fairlight and new digital instruments into the analogue world of synthesizer music was also a challenge.

– When I listen to Magnetic Fields today, I realise it has a much smaller sound than Oxygene and Equinoxe. It was in the beginning of the 80s and the sound of the 80s is the sound of a very poor digital era. The VHS era, if you like.

Magnetic Fields Part 1 takes up the entire side 1 of the album, and it’s 17 minutes long. But it’s still divided into three very different sections. Only one of which has ever been played live.

– Why isn’t Part 1 three songs?

– Because I wanted to make the statement that an album should be only one part. And I had never attempted that before. Prince did that once. In the middle of the CD era, he suddenly made an album (Lovesexy) with only one track, and no indexes. You had to listen to the whole thing, you couldn’t jump into the middle. I’ve always loved that idea. I never went that far, but that was the idea.

– Are you ever going to perform the third part of it live? Because a lot of fans really, really like it.

– I totally agree! Yeah, I think this kind of hysteric, speedy and crazy sequence would work great in concert. I agree, I should do it one day. Thank you for reminding me!

– The first time I heard Magnetic Fields Part 2, was in the Commodore 64 version of the game Bomb Jack.

– Yes! I loved that game.

– I’m sure they didn’t’ ask you for permission. Ben Daglish, a famous Commodore 64 composer, told me when I interviewed him that when he stole tunes from real life composers, he was 15. Nobody at the games company told him about publishing rights.

– Of course, they didn’t. I believe him. And I really loved it. Because I know a few other guys used other tracks from Magnetic Fields and made these low-fi minimalist 8 bit cover versions of my music. I really adored them!

– The first real version I heard of Part 2 was on The Concerts in China (1982) album. And when I finally heard the original, I was disappointed. Because I felt the China version has this energy that is missing from the original.

– I totally agree. And this is the reason why that I on the anthology Planet Jarre, I remixed that song, and used the solo and drums from the China version of the track. It’s funny, because you can ask a lot of artists, especially on the rock scene, about this. You do the studio version, and then you go on stage, and you’re improving it by playing it in a new and fresh way. It’s like the studio version is the demo, and then the song grows up and becomes an adult on stage. For Magnetic Fields 2, that is certainly true. You are the first one I talk to who has mentioned that, but we are in complete agreement.

The Concerts in China

We had now sort of moved on to the album The Concerts in China. In 1981. Jarre was the first western musician to perform there in modern times. He did five concerts in Bejing and Shanghai, and the resulting album was released a year later.

We had now sort of moved on to the album The Concerts in China. In 1981. Jarre was the first western musician to perform there in modern times. He did five concerts in Bejing and Shanghai, and the resulting album was released a year later.

– For me, that isn’t a live album. It’s obvious when listening to the Chinese radio broadcasts that you did a lot of work on the music in the studio when you came back. So, for me it’s more of a musical documentary of your experience in China.

– You know, that’s a perfect way to put it! You are absolutely right! For me, The Concerts in China was my next studio album after Magnetic Fields. It’s not a live record. Sure, it comes from a live experience, but it’s a concept album, like a studio album, with live elements. So, you are right, it’s like an audio documentary.

– My favourite track by you is on that album, namely Arpegiator. I like it when you play around with sounds, and still manage to create something so catchy. I was so happy that you included it on the Sequences section of Planet Jarre.

– And that is why I started the that section of the anthology with that track. It has a special magic, like its should be boring, but it’s not. It was a perfect way to start that part of the compilation.

I then, slightly embarrassed, admit to Jarre that it took me 20 years to realise that The Overture on that album is a slowed down version of opening section of Magnetic Fields Part 1.

– Yes! I was discussing with my band that was on stage with me in China about what we should open the concerts with. And the sound engineer made a mistake and he played Magnetic Fields 1 at half speed. And I said: “That’s it,” ha ha!

– And the worst part is, that on the China album, there is a track of bouncing ping pong balls, that lasts 21 seconds. And you’ve called that Magnetic Fields Part 1. The track is originally 17 minutes. Was it a joke?

– Yes, exactly, he he.

Zoolook

After the China album, Jarre started on one of his most ambitious recording projects. But while doing that, he was asked to write some music for an exhibition of modern art. The artists used items from supermarkets, and Jarre got the idea to make a statement: Since record companies had started selling records in supermarkets, like it was yoghurt or candy, Jarre decided to make something they couldn’t sell like this, namely a record where only one single copy would be made.

After the China album, Jarre started on one of his most ambitious recording projects. But while doing that, he was asked to write some music for an exhibition of modern art. The artists used items from supermarkets, and Jarre got the idea to make a statement: Since record companies had started selling records in supermarkets, like it was yoghurt or candy, Jarre decided to make something they couldn’t sell like this, namely a record where only one single copy would be made.

The album, called Music for Supermarkets (1983) was sold at an auction, and the master tape was burned. The night before the auction, Jarre played the record on radio Luxembourg, and the mp3s of the album you find online today is from that broadcast.

Jarre’s next regular album was Zoolook (1984), which is one of Jarre’s most important works. It consists of samples of the human voice in 30 languages. But they are mixed, processed and played through the Fairlight, and used as instruments. Even the strongest Jarre haters admits that this album has something going for it.

– Parts of the Music for Supermarkets album also resurfaced on Zoolook, didn’t it?

– I made Zoolook and Music for Supermarkets at the same time. It was the same sessions and the same moment. The recording of Zoolook took so long, I almost went crazy. It took me two years, including four months of mixing and I worked through four engineers. I used David Lord, Peter Gabriel’s sound engineer, he even lost a tooth, I think, during this process. It was crazy, haha.

– How? Did it come to blows in the studio?

– Yeah, and then they were all exhausted and I was still not happy with it. I had a very precise idea of Zoolook. I wanted this mad arrangement, with only vocals, and it was very difficult to achieve. I went to London and spent two months in Trident studios, and it was a disaster. I finally finished the mixing in my own studio. I remember David Lord came from Bath to help me. Every sound engineer is different, but Lord had this strange ideas, that really helped shape the sound of Peter Gabriel’s early albums. He put everything at 16 bit, pushed to the max, and I said that this would create a lot of hiss in the recording. But he said “no, no, it will create another layer.” Which was true, but I used the Fairlight, which is only 8 bit. So, it was useless to do what he did.

Finally, Jarre finished the mixing by himself. That’s when he realised he could actually mix his albums by himself, something he hadn’t done up to that point.

– In electronic music, mixing is just part of the composing process, really. But I didn’t really start doing that myself until I did the mixing of the compilation album Aero, which was mixed in 5.1 surround sound.

– You used the amazing bass player Marcus Miller on Zoolook. I interviewed him a few years back, and he said the session musicians in New York at the time only referred to you as “the French guy who goes ‘Mother fuckeeeeer.’

Jarre laughs out loud.

– Ha ha! But you know, Marcus Miller was very cool. He’s one of the best bass players in history, and when I asked him to play on my album, he played fantastically. And then I resampled every bass part he did and chopped it up in the Fairlight, ha ha. I apologised to him and said I hoped he didn’t mind.

– Actually, he told me the same thing. But he was cool with it, he really liked your music.

– He’s a great guy, and we are still friends. I was thinking about involving him in my Electronica project, but it didn’t happen. So, I hope on my next project, that I can do an electronic track with him. He is so talented. Just think, Miles Davis was a very difficult man to work with, even violent at times. And he let a kid, who was only 22 years at the time, produce one of his best albums, Tutu. That speaks volumes of Miller’s talents.

Rendez-Vous

The next album was Rendez-Vous (1986), and Jarre created that album while working on a huge concert held between the skyscrapers of Houston, Texas. The concert was a celebration of NASA and the 150th anniversary of Houston. 1,3 million people turned up at the concert. A world record at the time.

The next album was Rendez-Vous (1986), and Jarre created that album while working on a huge concert held between the skyscrapers of Houston, Texas. The concert was a celebration of NASA and the 150th anniversary of Houston. 1,3 million people turned up at the concert. A world record at the time.

– Quite a few of the themes on Rendes-Vouz came from singles you created for Gérard Lenorman in the mid-70s, what made you decide to reuse them?

– Rendez-Vous is the only album I composed to be performed on stage, because it was so mixed with the concert in Houston. And on that album, I have the anthem Rendez-Vous IV. And I think it was Michel Geiss, who came back after not being involved on Zoolook, who found it in the garbage. It was a demo I had made which I just didn’t like. But he insisted that we could do something interesting with that, so he basically saved that track.

Jarre explains that in those days he was also obsessed with the Stanley Kubrick movie, A Clockwork Orange.

– The soundtrack was done by Wendy Carlos, and I really liked the way she mixed this mad symphonic energy and music with electronics. So that’s how Rendez-Vous 2 became such a symphonic piece of music. And from that aspect, I think Rendez-Vous 2 works very well. The symphonic approach reminded me of those pop songs I did in the 70s, and I thought it could be really cool to build the music around those themes, created on the Eminent.

These days Jarre says that he has later learned that this particular track is used as music in churches.

– A journalist from a cultural magazine in France interviewed me, and he is doing a book about sacred music in modern times. And that kind of music doesn’t really exist anymore. And I’ve learned that Rendez-Vous 2 is used for weddings and for funerals. And I remember when I met Pope John Paul II, for the concert we did in Lyon after the concert in Houston, he mentioned Rendez-Vous 2 as sacred music. And I was so excited about that, because it was something I had never thought about it like that. But I love that composition. It has a nice structure, like a symphony or classical music, but with some big strong energy in it. Funeral for a Friend by Elton John has that kind of energy as well.

– Another thing a lot of people might not know, is that Rendez-Vous was ridiculously successful. It was in the top 50 on the Billboard 200, on the charts for months in the UK and it turns out it’s your second biggest selling album.

– It’s also my second biggest seller here in France as well. So yeah, you are right.

Jarre has a theory that the commercial and immediate music of Rendez-Vous IV is also a part of the explanation for the success. Something he’s not too keen on.

– Rendez-Vous IV has become a running joke within my entourage. They all say that if we play this, everybody is going to get up and clap and all that. And for me, it’s always a nightmare to play this track. I can’t even listen to it anymore. But wherever I’ve played it, everybody is just immediately into it. It’s almost mechanically, they all get up and start clapping and getting wild. Even the crew say “play this song.” And whenever we do, it’s working. But remember, I originally wanted to throw it out.

– Yeah, it’s not one of my favourites, truth be told.

– Oh, I agree with you, one hundred percent!

Revolutions

– On to Revolutions (1988). That was the first album you did that I was waiting for, and I love it for nostalgic reasons. But as you get older you get more cynical about your tastes…

– On to Revolutions (1988). That was the first album you did that I was waiting for, and I love it for nostalgic reasons. But as you get older you get more cynical about your tastes…

– Sure.

– … and today I realise that while you in the past created all the sounds yourself, on Revolutions you are mostly using the presets from the Roland D50 keyboard. I think I once described the album as the Roland D50 demo tape. What made you decide to make the album like that?

– You know, I really fell in love with the D50. For me, it was the anti Yamaha DX7 (digital keyboard used by everybody in the 80s, something that made it reviled for years). I know that Brian Eno will hate me for saying that, he loves the DX7. But I always hated it. I will never forgive Yamaha for killing Robert Moog, the ARP and all the classic synths by releasing this cheap junk.

Jarre also states that since the DX7 mimicked real instruments, it also created the ambiguous idea that synthesizers were only there to replace them.

– You could sound like an oboe, clarinet or a violin just by the push of a button. And the D50 for me was the total reverse. It had a very warm sound, even if it was very digital, so I became trapped by that. So, Revolutions was made mostly with this keyboard and the MPC60, from Akai. I did everything with them.

Even if Jarre on that album abandoned creating his own sounds, he stands by it.

– I often meet people who say that you shouldn’t use the presets, that you should process it and fix it yourself. I never understood that attitude. If you like the sound of the piano, you don’t try to change or twist the sound. You use it. The same goes for a violin or a clarinet. So, if there is a sound that you like in the synth, why should you go “no, since it’s in the instrument, we should not use it?’” That’s stupid.

– I like Revolutions because it came out in a very happy time of my life, so I have great nostalgic feelings for it.

– Exactly. And I really like this album too. There are some weird tracks on there, like Computer Weekend.

– Röyksopp told me they love that track.

– Really? The mosquito in that song is changing into a dog in the end, it’s really crazy, he he. And the title track has this great Islamic chant. You know, this track used to be played on radio in France, but there were so many right wingers who called and wrote in and complained, that the radio stations chickened out and stopped playing it.

– Since we are talking about this track: On the original release from 1988, there was a flute playing, and there was a different chant. But in 1990, you replaced the chant with a new one, and the flute was replaced by Arabic strings. Why?

– I had a problem with the flute player (Kudsi Erguner). He was originally from Turkey, and he also played on a Peter Gabriels record and with Brian Eno and myself. Then he sued everybody and said he was the co-composer and wanted royalties. That made me so angry that I decided on all future reissues that I would do a different version of it.

But it was, according to Jarre, a kind of blessing in disguise.

– It was also a good opportunity to change it, because I didn’t feel that the original quite worked. It was too much like World Music.

Stay tuned for Part 3 where we talking about paying the piano player to stop playing!

And there’s more. Here is a Spotify playlist that includes several of the songs discussed above:

What did you think of the second part? Any good? Something I should have asked? Leave a comment below!